Does this poll reflect the true preferences of the Dutch population?

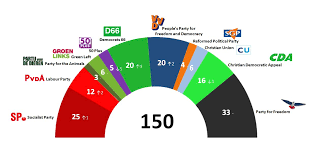

It is 13 March 2017, and the intermediate polls of the Dutch election suggest that it is going to be a close call between the Dutch Liberal Party (VVD) and the populist Party for Freedom (PVV). Who is going to be the biggest party of the Netherlands? Both parties are currently leading in the polls, and the winner will lead the formation of a new government, and most likely provide the new prime minister. So the stakes are high.Now suppose you don’t agree with the VVD. You prefer a more progressive party (such as GroenLinks or D66). However, one thing is for sure: you don’t want Geert Wilders (PVV) to win, let alone become the prime minister. What do you do, knowing that it is going to be a close call between the VVD and the PVV? Do you vote for the party that truly reflects your preferences (GroenLinks or D66 in this example), or do you vote for the Dutch Liberal Party, knowing that you prefer the Liberals to the Populists?

The last option (to vote ‘strategically’, or not on your most preferred candidate) is handed to you only because of the information you derived from the intermediate polls. It is only because you know what the result of the election will be – given that people will vote as indicated in the poll – that you can adjust your vote to it.

But this raises a question: do we want people to have the opportunity to vote strategically? Or differently: should we allow for intermediate polls?

Democracy as a reflection of voters true preferences

This basically comes down to another question: what do we want the election results to be a reflection of? Do we want the results to be a reflection of the true preferences of the members of a population (meaning: if 20% of the people most prefer the VVD, then the VVD will get 20% of the votes, etc)? Or do we want the results to be a reflection of both true preferences and insincere preferences (i.e., 30% of the people vote for the VVD, even though only 20% has the VVD as their preferred option, with the other 10% preferring the VVD to the PVV).

I think no reasonable person would say that we hold elections to elicit insincere preferences. After all: what is the point of a democratic election in case we want to end up with election results that don’t reflect the population’s true preferences? This might even contradict the notion of democracy itself. So we want to elicit the true preferences of voters through an election.

However, by publishing intermediate polls, we entice people to cast votes that don’t reflect their true preferences (i.e., voting for the most preferred candidate), as shown by the example above. Hence the election result will not be an accurate representation of people’s preferences, hence not an optimal form of democracy.

Bandwagon effect

But there is another argument to be made against polls: the bandwagon effect. The bandwagon effect implies that the rate of uptake of beliefs increase with the number of people already holding the belief. In practice this means that people, seeing a poll in which party x has more seats than party y, become more inclined to vote for party x than y, ceterus paribus. The result is that x gets more votes than it would have gotten in case the polls wouldn’t have been published, and another party – possibly y – less. Still: we end up a with election results that are different from what they would have been in case we didn’t publish the polls.

But you can also approach the issue from another angle by simply asking: what is the added value of polls? What do polls contribute to society? ‘Information,’ one could say: ‘information about the voting behaviour of the population.’ But what can we use this information for? We cannot use it to change the voting behaviour of others. So for that purpose it’s useless. It can only be used to change one’s own voting behaviour.

Banning polls

So it seems that the only contribution of polling is that it allows for changing your vote in light of the voting behaviour of others? Well, we have just established that this is not a good thing in a democracy. Therefore polling has no added value to society.

Assuming that all of the above is true, why then allow polls? Banning polls is not some far-fetched idea. It already happens in many countries, including France (on the day before the election) and Italy (15 days before the election).

And given the negative effect of polling on the democratic process, this might not be such a bad idea.