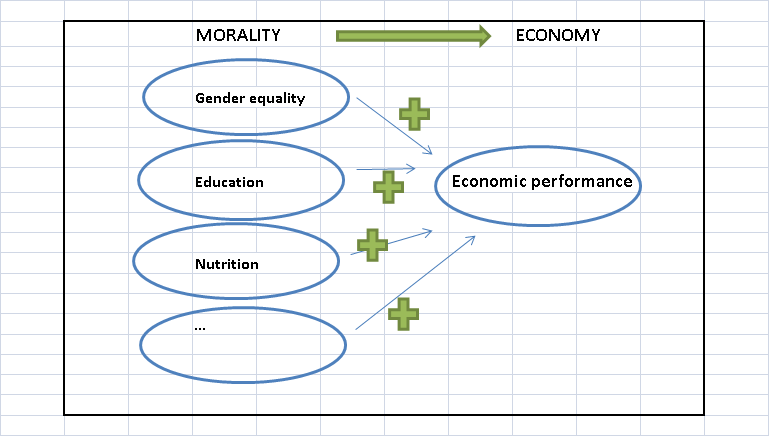

I think most of would agree that issues such as gender equality, education and malnutrition are important matters. Not only morally, in the sense that anyone of us should have the right to be treated equally, to receive education or to have proper feeding, but also because of their economic consequences. Studies have shown that gender inequality, lack of education and malnutrition affect the economy of a country negatively (see Figure 1). But fewer studies, at least none I could find, look at the relation the other way: what are the effects of economic development on gender inequality, education and malnutrition? Or more broadly: what are the effects of economic development on moral issues, instead of the other way around?

Let’s take gender equality, for example. I think it is reasonable to assume that when a country develops economically, the role of women in society will improve – in the sense that they are treated more equally to men. For suppose people have more disposable income, as a result of economic development. Then this money might allow families a sense of freedom that partially breaks down the traditional role division between the working man and housewife. The money might for example allow women to pursue their interests, whether this be education, painting or something else, thereby enabling them to develop in a manner similar to men.

Furthermore, economic development might reduce the number of children per family, thereby putting less pressure on either the man or woman to stay at home to care for the children. This enables both parties to participate more equally in, for example, the workplace.

Economic development might also increase the level of education in a society. In case there is a system of private schooling in place, this is obvious. For if people have more income to spend, they can spend more on the education of their children, thereby increasing the level of education received in society. Also, more income means more taxes. In case a country has public schooling, more taxes allows for a more elaborate educational system, thereby enhancing education. Also, when families have more income, their children might not have to do labour to increase the family’s income. This provides them with the time required for education.

Malnutrition; another problem. It is obvious how malnutrition might be bad for a country’s economy. But it is just as obvious how economic development might reduce malnutrition. After all: if people have more income to spend, they can spend more money on food, thereby decreasing the level of malnutrition. Furthermore, if an economy develops, the supply of food might increase, since there might be more economic demand for food. The food might also be cheaper due to increased mass production, hence increasing the availability of food for the common people.

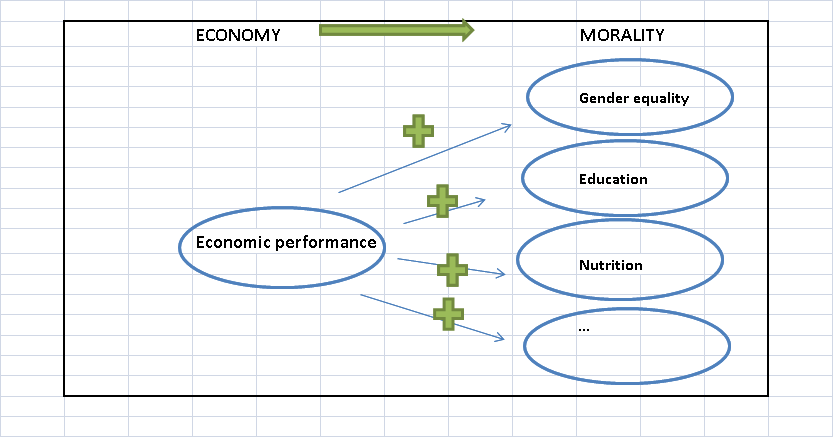

I am sure there are many other moral issues I didn’t deal with in this article (think about poverty, or child labour), but that affect both the economic development of a country and are affected by it. But what each of these matters appear to have in common is that they can be improved by improving the economic development of a society. Hence, in case you want to improve the well-being of a society, as many charities might want to do, you might be better of developing a society economically than to try and solve each moral issue one by one (see Figure 2). Because why choose the hard way when there might be a much simpler solution?

What do you think?