Most of the people that are in their early twenties seem to have no clue what profession to choose. They appear to be lost in the vast range of opportunities that they have to choose from. But why is that these ‘twenty-somethings’ feel this way? And how might they solve this issue?

From Stability to Instability back to Stability

Let’s start by taking a general perspective on the life of a twenty-something (being: a person who is in his twenties). The issue of what occupation to choose is by no means the only issue the twenty-something has to deal with. In general the following statement holds: as a twenty-something you are part of a transition-phase in life; a transition from stability, through instability, back to stability.

For the first part of her (I will say ‘her’ instead of ‘him/her’) life, the twenty-something-to-be did not have the freedom to choose whatever she believed was best. Or at least not concerning ‘big’ matters. It were the parents that took the decisions for her. They were the ones deciding what kindergarten, primary school, high school and – in some cases even – university she would attend. Also, within each of these institutions, the space to manoeuvre was limited. There were fixed programmes she had to attend. Resistance would have been futile, since her opinion was considered mostly irrelevant. The twenty-something-to-be was aware of her limited capacity to change the status quo, which made her suppress the need to reflect on the situation.

But it was not only regarding education that this (apparent) lack of control over her life had arisen. Decisions of where to live, what sports or musical instruments to play, and of course financial issues, were mostly if not exclusively handled by her parents. It was only when the twenty-something-to-be began attending university that freedom rose its head. And it is here that the trouble starts. Because even though freedom in itself is not what troubles the twenty-something-to-be, its counterpart – called ‘responsibility’ – is what makes her tremble. It is the responsibility for the consequences of her own actions that leaves her in a state of apathy. Now she has to take the decisions that up till that point in her life were made by everyone but her.

This phase of by times close to existential doubt ends when the twenty-something has gained long-term stability in her life again. Like being child, becoming a member of the working class implies the familiar presence of fixed rules and the limited need for self-reflection. Having made a choice of what occupation to pursue, and the act of actually pursuing this occupation, makes the twenty-something become immersed into a new institutional structure, making her rest in the faith of having found certainty after a very uncertain period in her life.

From Farmer to Professor

Back to the main issue. Many twenty-somethings appear to feel lost in the sense that they totally don’t know what profession to choose after finishing their studies. What more can we say about this feeling of ‘being lost’? The first thing we could notice is that this feeling appears to be a defining characteristic of what it means to be a twenty-something: it is a property that, by default, is present in any twenty-something’s set of basic characteristics. Given that it is a defining characteristic, it seems reasonable to assume that this feeling has been around forever. But this is not the case…

When I asked people in their fifties whether they knew what profession to choose when they were in their early twenties, they mostly replied negatively. However, when I asked the same question to my grandparents, they said the following: ‘Well, we didn’t really have a choice about what kind of job to do.’ My grandfather told to me that he grew up in a farmer’s family, and that from a very early age it was more or less ‘obvious’ that he would become a farmer himself. My grandmother, the eldest girl of thirteen children, was at the age of fourteen forced to quit her studies so that she could assist her mum in managing the ever-growing household. ‘But’, I asked my grandmother, ‘was there no-one in your family who attended university? ‘Yes, one of us did,’ she said, ‘He had the talent to do so.’ My grandmother assured me that this scarcity of university-attending students was very common among families in those days (70 years ago).

So it seems that the feeling of don’t knowing what profession to choose, as experienced by so many twenty-somethings today, is in fact a relatively new phenomenon. That is: until two generations ago this feeling wasn’t widely shared among twenty-somethings. And the reason for this is, as my grandparents explained, quite obvious: people didn’t effectively have a choice about what to do with their lives. I say ‘lives’ instead of ‘professional lives’, since also regarding other matters in life (religion and to a lesser extent marriage) the autonomy of twenty-somethings appeared to be limited. One could say that, in principle, my grandparents still had the option to deviate from what was expected of them. Assuming that they would have had the financial means to do so (which they didn’t), they could in principle indeed have done so. But in practice, given the social norms and values, they were either explicitly or implicitly discouraged from pursuing higher education or choosing a non-farming/housemaid job.

Nowadays the societies we grow up in are organized in a manner that is fundamentally different from the society of (let’s say) 70 years ago. Today, in contrast to two generations ago, the financial resources required for attending university are available to almost anyone who has the capacity and desire to attend university. Scholarships, government-funded studies, cheap loans and financially affluent parents are among the prime factors that have drastically reduced the chance of being unable to fund one’s higher education.

Next to a shift in the financing of studies, a society-wide ‘mental’ shift seems to have taken place. This is easily seen by taking a look at an arbitrary high school: a child who receives a certificate that allows him to pursue higher education is nowadays frowned upon if he decides not to do so. Whereas two generations ago a farmer-son would by default become a farm unless he had very good reasons not to do so, nowadays a farmer-son by default attends university unless he has very good reasons not to do so. This mental shift might be due to changes in our educational system. Today we have a system in which any child goes through a university-preparing teaching scheme, thereby maximizing their chance to attend university.

Note also that the financial- and mental shift might be interdependent: a shift in outlook towards children’s education might cause a change in educational funding, and vice versa.

Opportunities, opportunities, opportunities

But attending university is in itself no reason to become clueless about what kind of job to pursue. So explaining why it is that many more children today attend university than two generations ago does not explain why these people feel lost when reaching their twenties.

Although not a direct cause of ‘apathy’ among many twenty-somethings, one thing is for sure: pursuing higher education provides anyone with the potential to have more choices regarding what job to pursue. By attending university, the twenty-something knows that – without even looking at the labour market – she will be eligible for more occupations than she was before entering her studies. This fact implies that, when the twenty-something finally settles on a job, there will be more occupations (compared to her not having done her studies) she could have chosen but didn’t. It is the possibility that later on she might reflect upon her life and think ‘I could have chosen better’ that could be part of the explanation of the apathy among twenty-somethings. And since this possibility has increased over the last decades, so has the apathy among twenty-somethings.

Another consequence of higher education that isn’t necessary obvious is that over the course of her education the twenty-something’s interests might change; that is, the occupations/sciences the twenty-something found interesting before embarking on her studies, she might not find interesting anymore when she has finished her educational process. For example: she might finish her first year of university wanting to become a business-consultant, only realizing after finishing her second year (which included courses in philosophy) that she is much more passionate about philosophy. It is not the change in what she finds interesting that makes the twenty-something doubt about what kind of profession to pursue, as much as having experienced that whatever it is that she finds interesting can in fact change. And the idea that – as in education – she could choose a job that she likes now but possibly not anymore in the future increases her uncertainty regarding what job the choose.

Education is merely one of the factors making a twenty-something doubt her occupational choice; it is the part that transforms her from ‘the inside out’. Now, let’s take a look at how the outside world (i.e., the world external to the twenty-something’s mind and body) contributes to the doubts held by the 21st century twenty-something. There are a number of reasons due to the outside world because of which twenty-somethings nowadays have such a hard time choosing an occupation. First of all, because of the ever-increasing specialization, there are simply many more occupations she has to choose from than there were two generations ago. Whereas in the past there might not have been (many) alternatives next to becoming a farmer, nowadays there are literally thousands and thousands of occupations she has to (not only can) choose from, and each of these occupations is partitioned into many areas of specialization.

Also, because of globalization and the prominence of the internet, many barriers have been taken away that could have prevented the twenty-something from 20 years ago from doing whatever it was that she wanted to do. In other words: there is no excuse anymore for not starting a business or for not working at a big firm on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean. There is nothing but her own courage to withhold her from pursuing her aspirations; a scary thought. To exemplify this, let’s return to the case of my grandmother. It was clear to her that, after assisting her mum, she would marry a farmer and take care of his household. She might not have liked having few – if any – options about what ‘job’ to pursue, but that was simply the way it was. A positive side effect from her having limited options was that she was ripped of the responsibility to decide what her future would (not) come to look like. It is in this sense that she might have been lucky, for she was saved from the daunting soul-searching journey so many twenty-somethings today are forced to go through.

Options

I have mentioned the word ‘options’ more than once. I dare to say that most people believe that having options is a good thing. Certain philosophers even claim that autonomy (as in having the freedom to decide what one’s life goals are, how to pursue them and whether or not to actually pursue them) is intrinsically valuable. This is a conviction I do not necessarily share.

Like anything, having options becomes a problem if one faces too many options. And I believe this is the issue today’s twenty-somethings are facing. Specialization, the internet et cetera have drastically increased the number of career-options a twenty-something could fulfill; they have increased them to such an extent that she, being a rationally bounded creature (as any human being is), is both unable to overview all of them, let alone compare each option to each other option. Although impossible, the latter is required in order to make an optimal decision. After all, how can the twenty-something ever come to know whether she has made the best choice if she hasn’t considered/compared all options?

Next to there being too many options, there might be options that are incomparable. Why? Because the values they allow one to achieve are not ‘convertible to the same currency’. Think about the choice between becoming a charity worker or an investment banker. The first job might be better in terms of helping those who need help; the second might be better in terms of utilizing one’s intellectual capabilities. But which one of these criteria is most important, and why? And how much more important? These are questions that do not have an obvious (if any) answer.

Back to the claim that having options is not necessarily a good thing. Let’s return to the case of the farmer’s son. Given that the farmer’s son knows that he has no choice but to become a farmer, he is likely to never experience the regret (or the apathy caused by the prospect of regret) that today’s twenty-something faces. Nevertheless, when we analyse the farmer’s son situation, and come to see that his only ‘option’ is to become a farmer, we tend to feel sorry for him. It seems like having only one option is really not having an option at all, making his ‘choice’ to become a farmer look more like an act of coercion than an act of free will, contradicting the autonomy many of us find so valuable. However, due to this same lack of options, the farmer’s son will have no choice but to rest in his faith. He simply cannot do anything to alter his situation: he can only accept or resist his situation. He will accept his situation, because not doing so would decrease his happiness.

For today’s twenty-something it is (almost) impossible to rest in her faith, since, due to the autonomy has but the farmer’s son didn’t, she is faced with a never-ending string of opportunities. This makes it very difficult for her to be satisfied with any particular option. After all, it is very likely that, among all the opportunities out there, there is one that would be preferred to this one, if only she would find – or would have found – it. It is this observation that leaves her in a perpetual state of downgrading the options that are effectively available to her, and thereby her happiness. So even though the twenty-something of today has more autonomy than the farmer’s son of two generations ago, it does not follow that the twenty-something will be happier than the farmer’s son. In other words: more choices don’t necessarily imply more happiness.

Intuition

In the last section we stumbled upon a non-trivial observation. Namely: because of the vastness of opportunities the twenty-something faces and her limited rational capacities to oversee all of them, rationality alone is not sufficient for the twenty-something to choose the ‘best’ option. It is after all impossible to compare all options, hence to know if – and when – she found the best option.

But even though it appears impossible to choose the best option, one thing is for sure: she has to make a decision. Even the decision not to pursue a career is a choice, and should therefore be compared against other options. Since it is impossible to compare all occupations in terms of how well they score on all relevant criteria (loan, chance to develop yourself etc.), the twenty-something has to make use of some sort of ‘selection device’, that pre-selects a subset of the set of all occupations. This is required to allow her to compare each member of this smaller set to each other (based on how well they fare with regard to the relevant criteria). By doing this, she might be able to find a ‘local maximum’: that is, the best occupation given this limited set of occupations. That is all she can hope for given the rationally limited creature that she is.

Assuming that she doesn’t want to randomly pre-select some occupations, the twenty-something has to determine the criteria she finds most relevant for composing this pre-selection. However, this course of action might prove to be unsuccessful, due to the incomparability of criteria (money versus altruism, for example). But this problem might be circumvented.

The answer to picking the criteria must come from something ‘non-rational’ or ‘irrational’ – although I find the latter term misleading, as I will explain later. The non-rational element, on the basis of which the twenty-something might be able to execute her rational machinery, should make clear on a very basic whatever she finds valuable and what not: that is, it should provide her with her most basic wants. These basic wants must come from a place within the twenty-something that holds the instantiating power to all her actions. Let’s call this place the ‘unconscious mind’.

But the unconscious mind’s instantiating power comes at a cost: it is inaccessible to the conscious mind. And since rationality resides within the conscious mind, neither is it accessible to rational deliberation. Now, although the unconscious mind is not accessible, its ‘output’ is. Its output is what we call ‘intuition’, and manifests itself through those inexplicable feelings of something just ‘feeling right’ or ‘feeling wrong’. Although our intuition doesn’t come with any reason for why it is that something feels good or bad, it does something that is at least as important: it provides us with the values we need to choose what we want.

Intuition in practice

Since intuition is non-rational, it cannot communicate through thoughts: it communicates solely through feelings. But how should the twenty-something go about interpreting these feelings? How does she know what feelings will lead her in the right direction, whatever this might be, and which in the wrong direction? The answer is simple: through trial and error.

There are various reasons why trial and error seems to be the best, if not the only, way for the twenty-something to go about finding the (locally) best occupation. As I explained before, the twenty-something isn’t born with a fixed set of desires; nor with a fixed set of capabilities. Throughout her life, she, for whatever reason, might decide on developing certain skills (e.g., playing piano or mathematics), and, parallel to these developments, she will develop a corresponding level of affinity with practicing these skills.

Next to developing affinity, or ‘preferences’, for practicing certain skills, the act of practicing skills also shows the twenty-something her relative ability in practicing these skills. For example: someone who, after comparing her skills, finds herself to be relatively good in a certain subject area (e.g., mathematics). Then, after having looked at her own capabilities, the twenty-something can decide to look at how her abilities compare to those of others. Based on this observation, she can find out in what field she could potentially make the greatest contribution to society. This is obviously beneficial to society, but just as much to the twenty-something herself, for it is because of the fact that she knows that she does what she is best at – either in terms of her own skills or compared to others – that any negative feelings, that might result from questioning the usage of her capacities, will be minimized.

Furthermore, a nice feature of the twenty-something looking for her relatively best skill is that she is guaranteed to find one. Even those who are negatively minded are at least sure to have a least bad capability.

This observation naturally leads us to the following conclusion: the twenty-something has to engage in all sorts of activities or occupations in order to obtain her preferences for them. Because she lacks any absolute sense of what she likes most, she cannot a priori (that is, before undertaking any action) know what skill, and hence what occupation, suits her best. Given this conceptual background, it might be that her feeling of don’t-knowing-what-to-do is in fact an indicator of the fact that the twenty-something has spent too much time looking for this non-existent absolute preference ranking (‘soul-searching’, as one might call it), and too little time actually developing such preferences.This also leads us to what might be a solution to the twenty-something’s apathy. Namely: by engaging in different activities or subject areas, and developing various skills, the twenty-something creates as well as experiences her preferences towards the respective subject areas or skills. Hence this is the first step away from apathy.

‘But’, the twenty-something might ask, ‘how do I know when to stop the trial-and-error process?’ One can look at this process from an economical point of view: the act of finding a satisfying occupation is nothing but a cost-benefit analysis. Given the inevitable diminishing marginal utility of any effort put into the trial-and-error process, surely a point will be reached at which the twenty-something’s hope of finding the best occupation and her satisfaction with her currently preferred option cancel out. It is at that point that the truly best occupation, in terms of maximizing utility, has been found.

The rationality of being non-rational

We have established that rationality alone is not sufficient for the twenty-something to choose a satisfying occupation. In order to find such an occupation, a ‘non-rational’ component must be introduced: the unconscious mind. But somehow we seem to have difficulties with our choices being (at least partially) determined by a non-rational element.

It might very well be that, in this 21th world we’re living in, rationality is put on a pedestal, and everything non-rational is considered a source of errors, leading us astray from our objectives. We are taught to ignore our intuitions wherever possible; at least when there are ‘rational’ arguments at hand. This might be due to the fact that non-rational factors are beyond our control, thereby making us to some extent a slave to our feelings, thus decreasing our perceived autonomy. But you could ask yourself the question: what is the value of being in control if your ‘controlled’ life doesn’t cohere with your intuitions? What if letting go of control is required in order to explore the full range of opportunities, thereby unlocking the door behind which the realm of unexplored potential resides?

If any, the message of this article is that value cannot be rationally constructed. The ways through which we might achieve what we value can be rationally constructed, but the value itself comes from a domain that is distinct from any rational – or even conscious – part of ourselves. Although this might be difficult to accept for any person taught to think carefully about any choice in life, it is a prerequisite for embarking on the rational process: first you have to accept what you value in order to try and set out a path to reach that which you value.

So one could say that being non-rational, to a certain extent at least, is a prerequisite for being rational. If you don’t allow yourself to act on non-rational impulses, you have no basis on which to cast the rational power, thereby excluding the possibility of doing that which you might value. And isn’t that what we all want to do? To do what we value? If so, we might as well embrace the non-rational, or even stronger: claim that it is rational to be irrational.

Love

In this last section I want to focus at another potential source of uncertainty for any twenty-something: love. Being in-between the period of life in which love was yet unable to be experienced, and the part in life in which love is deemed to be a relic of the past (or ‘has changed into mutual compassion’), there is this period in which the twenty-something is likely to feel the need to find a future life partner.

But what is love? What characteristics does the twenty-something’s future partner need to have? Are the negative aspects of the relationship she is currently in likely to fade away over time? Or are they are structural component of the chemistry she is (not) having with her current partner? And how to distinguish between the two? If she would end the relationship now, would it leave her forever with a feeling of deep regret for having let this opportunity pass by? Or will it – in retrospect – proof to be a milestone on her way to finding that perfect partner with whom she will spend the rest of her life?

These are questions that any twenty-something is likely to ask herself at a certain point in time. It seems to be the case that most people get married around the age of 30, often being the culmination of a relationship that has been underway for at least a couple of years. A quick calculation shows that, assuming the latter to be true, the twenty-something should meet her life partner not much later than the age of 25. And the more this age approaches, the stronger becomes the twenty-something’s doubt about the status of her current relationship, or, if she doesn’t currently have a partner, the stronger gets the urge to find a potential life partner.

However, the great problem with any romantic relationship is that only in retrospect can be determined whether it has been a good decision to continue the relationship. It might be the case that, at this point in time, the twenty-something and her partner experience struggles that will grow larger and larger as time goes by. But the question of whether these struggles are merely obstacles to overcome on the road to living happily ever after, or that they are symptoms of a profound mismatch between the two, is impossible to answer up front. Here too it seems that only intuition can guide the way, since the experiences that could provide the twenty-something with the relevant information lie in the future, and are thus (for now; the moment we’re always living in) beyond her experience.

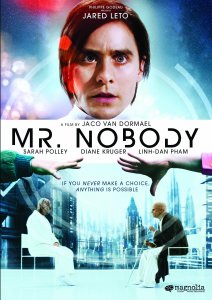

I have just seen the movie ‘Mr. Nobody’, and I recommend anyone who is interested in philosophy to go see this movie. It’s by far the most philosophical and mind-boggling movie I have ever seen. The movie shows, among other things, the lack of control we have over the course of our lives. Each and every moment in life you make decisions that make you go one way or another, and this string of decisions is – in fact – what we call our lives. The movie also portrays a rather deterministic view on life. The butterfly effect, as explicated in the movie, is the prime example of this; even the smallest change in the course of history can make our lives turn out completely different from what it would have been without the change.

I have just seen the movie ‘Mr. Nobody’, and I recommend anyone who is interested in philosophy to go see this movie. It’s by far the most philosophical and mind-boggling movie I have ever seen. The movie shows, among other things, the lack of control we have over the course of our lives. Each and every moment in life you make decisions that make you go one way or another, and this string of decisions is – in fact – what we call our lives. The movie also portrays a rather deterministic view on life. The butterfly effect, as explicated in the movie, is the prime example of this; even the smallest change in the course of history can make our lives turn out completely different from what it would have been without the change.