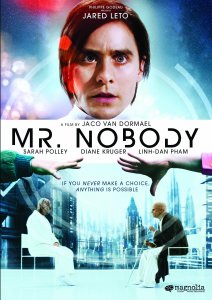

I have just seen the movie ‘Mr. Nobody’, and I recommend anyone who is interested in philosophy to go see this movie. It’s by far the most philosophical and mind-boggling movie I have ever seen. The movie shows, among other things, the lack of control we have over the course of our lives. Each and every moment in life you make decisions that make you go one way or another, and this string of decisions is – in fact – what we call our lives. The movie also portrays a rather deterministic view on life. The butterfly effect, as explicated in the movie, is the prime example of this; even the smallest change in the course of history can make our lives turn out completely different from what it would have been without the change.

I have just seen the movie ‘Mr. Nobody’, and I recommend anyone who is interested in philosophy to go see this movie. It’s by far the most philosophical and mind-boggling movie I have ever seen. The movie shows, among other things, the lack of control we have over the course of our lives. Each and every moment in life you make decisions that make you go one way or another, and this string of decisions is – in fact – what we call our lives. The movie also portrays a rather deterministic view on life. The butterfly effect, as explicated in the movie, is the prime example of this; even the smallest change in the course of history can make our lives turn out completely different from what it would have been without the change.

Each movie can be interpreted in multiple ways, and that surely goes for Mr. Nobody. Nonetheless, I believe that from a philosophical point of view there is at least one issue that is very prominent, and that is the struggle between free will on the one hand and determinism on the other.

What will follow might be hard to grasp for those who have not seen the movie yet. Therefore I assume that, by this point, you have seen the movie. At first sight, Mr. Nobody is all about choices. That is: what will happen in Nemo’s life given that he has made a certain choice (e.g., to either jump on the train or not). The fact that there is this possibility of at least two different worlds Nemo could live in (i.e., the one with his mother and the one with his father) seems to imply that Nemo had (in retrospect) the possibility of choosing either of the options. And it is this element of what seems to be some form of autonomy (the ‘free will’ element) that returns frequently in the movie. Another instance of it can be found in his meeting with Elise on her doorstep. In one ‘life’ Nemo expresses his feelings for Elise, after which they get married and get children. In another life, Nemo does not express his feelings, and his potential future with Elise never occurs.

However, the true question I asked myself after watching this movie was: does Nemo in fact have the possibility to choose? Or are his ‘choices’ predetermined by whatever it is that occurs in his environment? An instance of the latter could be found in Nemo loosing Anna’s number because the paper he wrote her number on becomes wet (and therefore unreadable). In other words, these circumstances seem to force (or at least push) Nemo in the direction of a life without Anna; a circumstance that ultimately results from an unemployed Brazilian boiling an egg, which is another instance of the butterfly effect. So although it might appear that Nemo has the opportunity to make choices, it might in fact be that ‘the world’ (as in the environment he is living in) has already made this choice for him.

The struggle between the apparent existence of free will and the ‘true’ deterministic nature of the world is just one among many philosophical issues raised by this movie. Another is that of the arrow of time: the fact that we cannot alter the past but can influence the future. It is this aspect of time (the fact that it moves in one direction only) that makes the free will versus determinism issue so difficult (if not impossible) to resolve. After all, if we could simply go back in time, and see whether we would have behaved in the same manner, irrespective of the non-occurrence of any circumstances, we might get a much better feel on the nature of free will. After all, if we would happen to act more or less the same, irrespective of the circumstances we would be put into, we would appear to have something resembling free-will. If not, determinism might be the more realistic option.

Nonetheless, this is a very interesting movie whom those interested in philosophy will surely enjoy. And to those who have seen it I ask: what did you think of it?