I am a professional trader. That means that I buy and sell stocks for a living. And since I am a so-called ‘day trader’, the buying and selling have to happen within one day. This means that I am extremely short term focused: I try to anticipate where a stock will be at within five minutes or an hour from now, instead of five years.

As a trader, you obviously want to buy a stock as cheaply as possible, and to sell it for as much as possible. But if you think that studying financial documents and finding out what companies appear undervalued will help you in trading, you are only very partially right. Much more important, I dare to say, is understanding and using human psychology. And when you zoom in from years to days to minutes to seconds, the more important human psychology becomes.

Let me give you an example of how big hedge funds (which I certainly do not belong to) seem to use human psychology to increase their profits. I say ‘seem’, because I cannot prove this. If only because I don’t know who is buying or selling at any moment in time (but I can see what hedge funds own what stocks, and when they bought/sold). But given my everyday experience with movements in price, and applying common sense, I am reasonably certain.

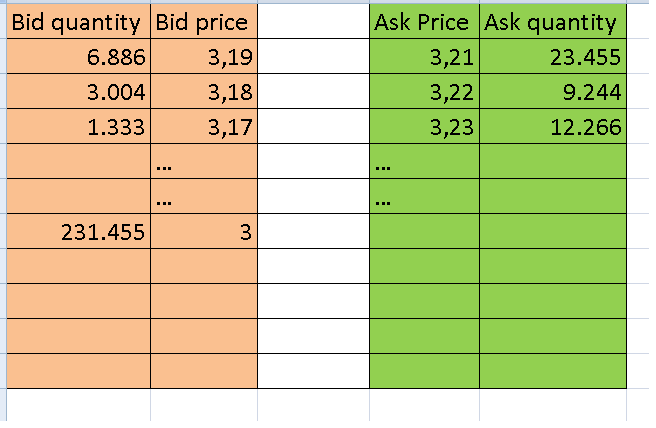

Suppose there is a stock trading a little above $3. Last time it went to $3, it recovered to $10 within three years, and to $55 within six. Last year the stock was priced at $10, and ten years ago it was priced at $55. Therefore it looks cheap (irrespective of the fundamentals of the company). Hedge funds assume that many people are willing to buy at this price. Assume that many people do. Now hedge funds, with practically unlimited financial resources, come in. They create a level of resistance in the price. They do so by offering a practically infinite amount of stocks at best offer (being the lowest price at which people are willing to sell the stock: $3,21 in Table 1). By doing this, they create an upper limit in the price, since before the price can increase, all the stocks at best offer have to be bought, which is practically impossible given that the hedge funds have so much selling power compared to the rest.

Now, since the price cannot go up, it will go down at a certain point. Be it because of algorithms trying to maintain certain correlations with indices, or because the hedge funds actively sell stocks at successive levels of best bid (the highest price at which people are willing to buy the stock: 3,19, 3,18 etc. in Table 1). Through doing this, the price will decrease to let’s say $3: a ‘psychological level’ in the stock. Many of the people who bought the stock thought it would never go under $3. Now people get anxious. Then the hedge funds give the final blow, and push through the $3. Now people start to panic – “maybe the stock will go to $2!”. They start selling the stock ‘at market’, meaning regardless of the price.

Now the hedge funds can buy the stock for less than $3 from the people who are selling at market, either to go ‘long’ (to have stocks), or to cover their shorts. See Figure 1 for a graphical display of this chain of events. Combine this with the fact that high frequency traders (acting on behalf of hedge funds) can change the order book in less than the blink of an eye (thereby changing the quantities on bid and offer), they can very quickly change the price of a stock. The price of a stock is after all nothing more than the price paid for the stock in the last transaction: so if you very quickly pull away successive levels of best bid, the next person selling at market will do so at a (much) lower price, meaning that the hedge funds buy at a lower price than the general public.

Now the hedge funds have bought their stocks, they pull back, and let the market do the rest.